Musei Vaticani, 2010-2013

It is not true that our eyes see everything. They see only what our brain orders them to see. Every time our gaze shifts it is a choice, and every choice is a critical and/or emotional interpretation of the visible truth. Christoph Brech’s photography book invites and justifies reflections of this kind.

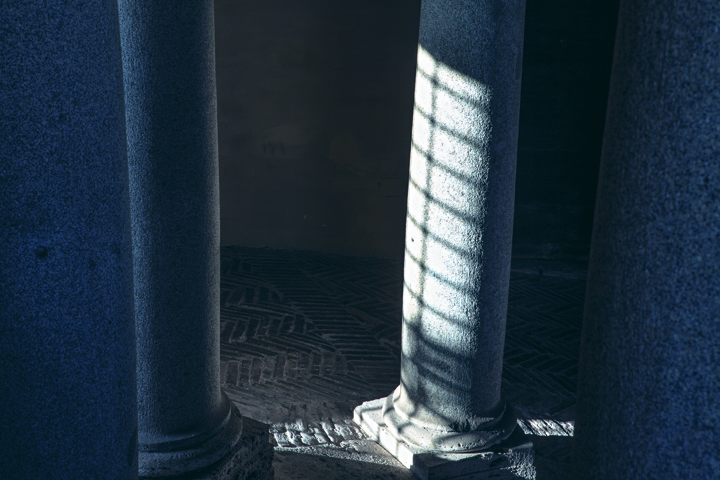

His visit to the Vatican Museums begins with visions of majestic classical beauty: the dome of St Peter’s, Rome seen from the terrace designed by Pirro Ligorio. Immediately after, however, when the eye of the photographer enters the museum, the vision is shattered into virtually endless perceptions. One after the other, we meet with images as diverse as they are unexpected: a horse’s head in The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila in Raphael’s Room of Heliodorus, a fragment of fake yellow gold drapery in the Sistine Chapel, rows of Roman busts in the storage area under the Cortile delle Corazze, the broken legs of a Roman statue against a window frame in the light of the Roman summer.

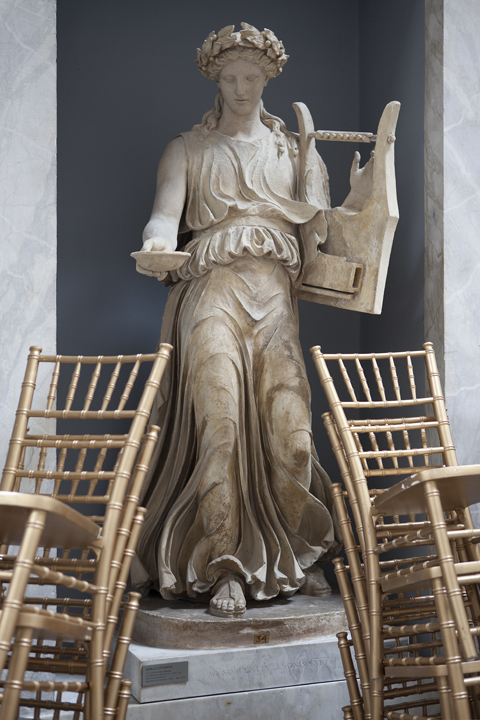

The bust of an emperor might lie beside a pile of chairs. Bramante’s staircase might draw us dizzily. Statues of Egyptian gods in shiny black basalt might emerge from the darkness. If I had to sum up Christoph Brech’s work, I would say that he encapsulates the two deepest currents of the German spirit—Expressionism and Romanticism—conveying both with refined elegance and remarkable poetic sensibility.

Antonio Paolucci, Director of the Vatican Museums (text for Unrestricted Views, Sieveking 2015)